Long before electric vehicles hit the mainstream, engineers were chasing a different kind of dream: cars that didn’t just drive—they hovered. In the 1950s, the Curtiss-Wright Air Car 2500 promised a roadless future, where travel happened on a cushion of air. It didn’t run on clean energy, and it wasn’t exactly practical, but it captured the same futuristic spirit that’s driving EV innovation today. What happened to it—and why it failed—offers a surprising look at how far we’ve come, and how far we still have to go.

The Birth of the Air Car 2500

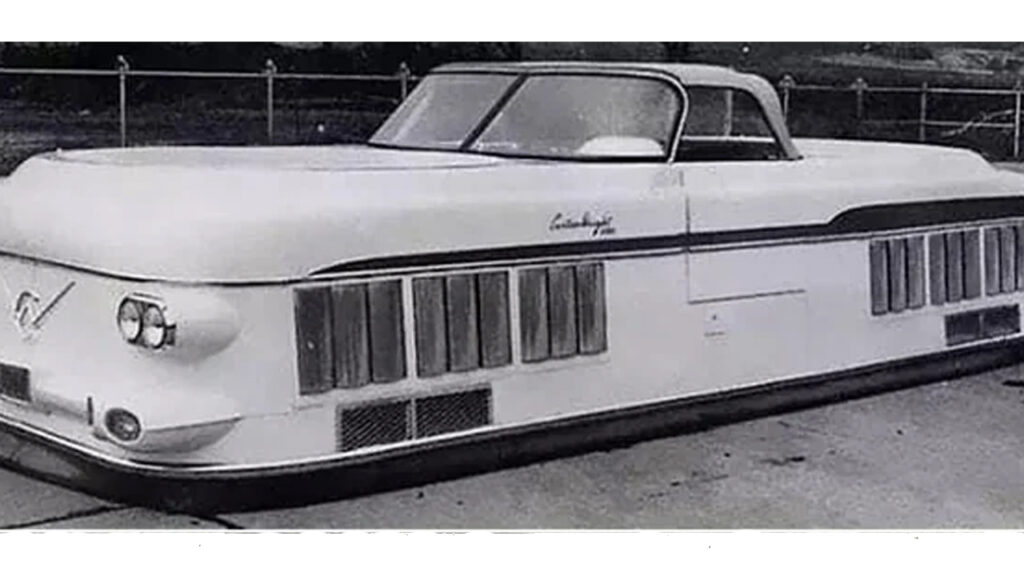

In the late 1950s, Curtiss-Wright, an aviation company, tried to reimagine personal transportation with the Air Car 2500. This four-passenger ground-effect vehicle hovered about a foot off the ground using two Lycoming aircraft engines. It was meant to skip over traffic, ignore roads, and handle light off-roading with ease—basically, the flying car everyone thought we’d have by now.

But there were problems from the start. The Air Car could only operate on smooth, flat surfaces, struggled with inclines, and made a ton of noise. While EVs today quietly handle diverse terrain and real-world road use, the Air Car was more sci-fi than street-ready (Source: U.S. Army Transportation Museum).

Military Interest and Testing

The U.S. Army picked up a couple of Air Cars to test for amphibious and off-road use. Renamed the Ground Effects Machine (GEM), it was floated as a vehicle that could glide over land and water. In theory, it could’ve been a tool for rapid transport in rough environments—kind of like a Hummer with hover abilities.

In practice, it couldn’t haul much, didn’t work well on uneven surfaces, and needed perfect conditions to perform. So while it looked futuristic, it lacked the reliability that today’s EV platforms are aiming for. The Army walked away, and so did funding (Source: U.S. Army Transportation Museum).

Public Reception and Market Challenges

Curtiss-Wright hoped this would become the next big thing in personal travel. But in the real world, the Air Car was loud, expensive, and hard to justify. At $15,000 in 1959—roughly $140,000 in today’s money—it wasn’t built for mass adoption (Source: The New Yorker).

That’s where it sharply contrasts with EVs today, which have increasingly prioritized affordability, sustainability, and day-to-day practicality. The Air Car, by comparison, looked cool but didn’t solve real problems for real people. It faded fast.

Legacy and Preservation

One of the few Air Cars still exists at the U.S. Army Transportation Museum in Virginia. It’s a relic of a different vision for future transport—more about escape and spectacle than emissions or infrastructure. It reminds us that chasing the “next big thing” in mobility only works if you actually meet everyday needs (Source: U.S. Army Transportation Museum).

Today’s EVs may not fly (yet), but they’ve learned something the Air Car didn’t: the tech has to work, and it has to work for everyone. Otherwise, even a hovercraft with seats isn’t enough.

Design and Technical Details

The Air Car was powered by two 180-horsepower aircraft engines spinning ducted fans that created a lift cushion. Its welded steel frame and molded panels gave it a car-like look, but under the hood, it had more in common with an aircraft than a sedan.

Unlike modern EVs with intuitive software and quiet, low-maintenance motors, the Air Car was complex to operate and brutally loud. Its top speed maxed out around 38 mph, and it couldn’t handle more than a 6% incline (Source: Curbside Classic).

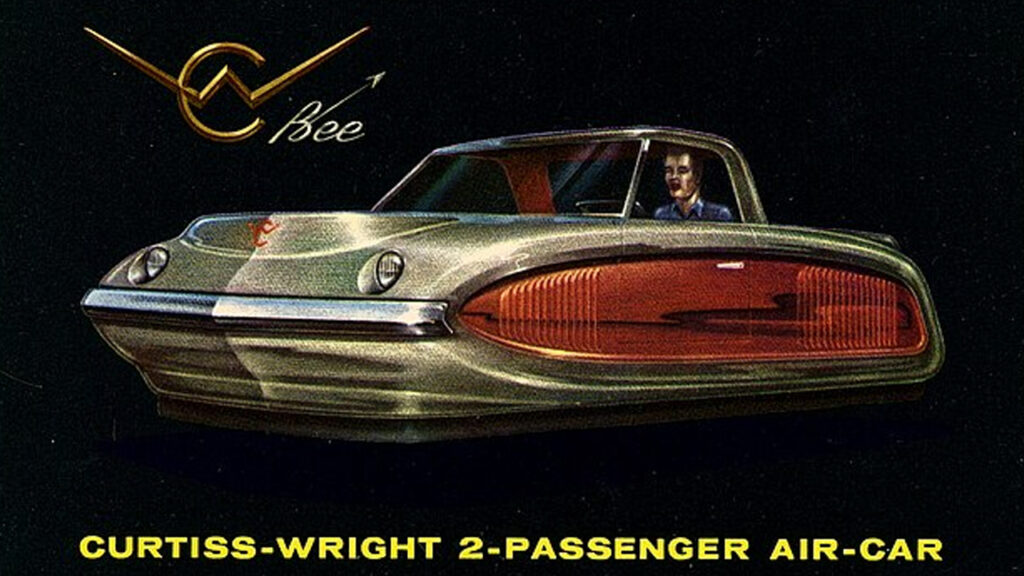

Variants and Commercial Aspirations

Curtiss-Wright had big plans: a family model, a two-seater “Bee,” and even a utility version. Each was supposed to bring this hover concept to a different kind of buyer. The compact version was cheaper—around $6,000—but still too niche to find real traction.

None of it stuck. Without infrastructure, government buy-in, or consumer demand, the Air Car quietly disappeared. Contrast that with the rise of EVs, where demand, policy, and charging networks are aligning to support real adoption (Source: Carstyling.ru).